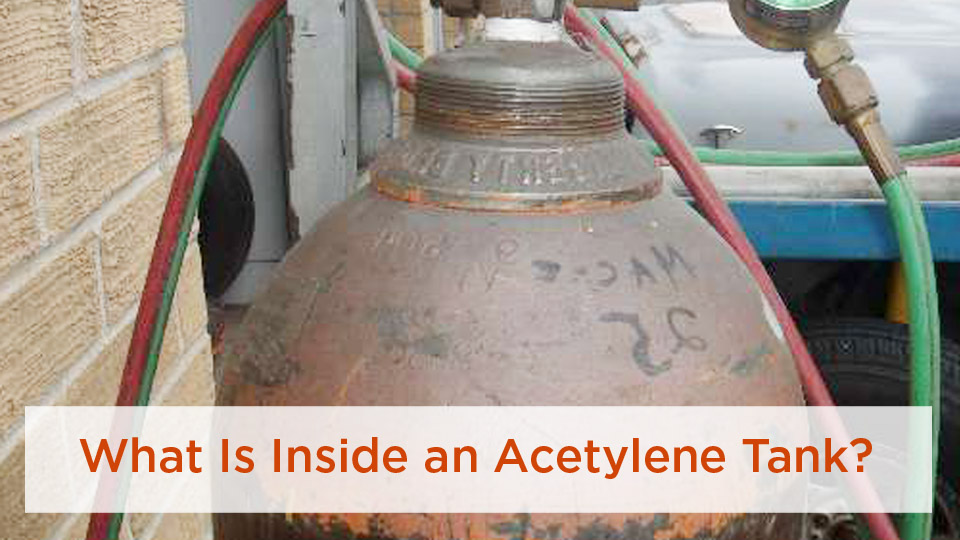

When you first look at an acetylene tank, it’s easy to assume it’s just a solid cylinder of compressed gas like an argon or CO₂ bottle. But any welder who’s spent time cutting steel plate, prepping joints for MIG vs TIG, or running filler rods on stainless knows there’s something different about these tanks.

Instead of being filled with pure gas under high pressure, an acetylene cylinder contains a porous mass saturated with a solvent (most commonly acetone, sometimes dimethylformamide/DMF). The acetylene gas is dissolved in that solvent and stabilized inside the porous structure.[5][7]

This design often surprises beginners who expect acetylene to behave like shielding gases, but understanding what’s really inside affects everything from weld safety and flame control to overall job cost and structural quality. If you’ve ever wondered why handling an acetylene tank requires extra care, keep reading — this guide breaks it down in plain shop talk so you can weld smarter and avoid costly mistakes.

What Exactly Goes Into an Acetylene Cylinder?

Pop the lid off that tank in your mind, and you won’t find just swirling gas. Acetylene cylinders are like a high-stakes sponge—packed tight to stay safe. At the heart is acetylene gas (C2H2), colorless in pure form but often described as having a garlic-like smell when contaminated by trace impurities from production.[11] Here’s the kicker: it isn’t floating free. It’s dissolved in solvent (typically acetone; sometimes DMF), which the porous mass holds uniformly throughout the cylinder.[5][7]

The porous monolithic filler—commonly a calcium-silicate–type material engineered with a high void fraction—distributes the solvent and gas evenly and resists the spread of heat or flame inside the cylinder.[5] Manufacturers permanently install and bake this mass during production so it stays put through transport and use.

You’ll sometimes see illustrative breakdowns (e.g., solid mass on the order of ~10% of the internal volume with the balance comprised of voids filled by solvent and dissolved gas, plus a small free-gas “reserve” at the top). Treat those as typical examples, not exact specs for every cylinder.[5]

Why bother with this design? Because acetylene becomes hazardous if used above 15 psig (≈30 psia absolute); dissolving it in solvent inside a porous mass allows safe storage at a typical settled cylinder pressure around 250 psig at 70 °F while maintaining stability.[1][6][9]

Why Dissolve Acetylene in a Solvent? The Stability Science

On its own, acetylene can undergo exothermic decomposition under heat, shock, or pressure. Dissolving it in acetone (or DMF) and holding it within a fine, cool porous network radically reduces that risk by spreading heat and preventing large pockets of free gas.[5]

In practice, what matters to you at the torch is draw behavior. Don’t overdraw the cylinder: a common rule of thumb is to limit withdrawal to about 1/7 of the cylinder’s capacity per hour (and some manufacturers recommend closer to 1/10, especially for small cylinders) to avoid pulling solvent into the lines.[10]

Signs you’re overdrawing include yellowing or sooty flames and erratic pressure. Let the cylinder stand upright at ambient temperature and reduce flow; solvent carryover typically clears once the withdrawal rate is back within limits.[10]

The Porous Filler Material: Your Tank’s Unsung Hero

Ever wonder why acetylene tanks feel heavier than oxygen bottles of the same size? The rigid, fire-resistant filler is molded to fit every nook so the solvent saturates millions of micro-pores and the dissolved gas is distributed evenly. In a flashback, this mass helps cool and quench the event internally, buying critical time.[5]

Suspect the mass or solvent has shifted (e.g., after a cylinder was laid on its side)? Store it upright and allow time for resettlement before use. Many suppliers advise at least one hour upright before opening if a cylinder has been horizontal—always follow your supplier’s guidance.[6]

How Acetylene Cylinders Are Made and Filled: From Factory to Your Shop

Cylinder shells are built to U.S. DOT specifications (commonly DOT-8 or DOT-8AL) with a service pressure of 250 psig. They undergo hydrostatic testing and must meet burst criteria defined in federal regulations (e.g., test pressure ≥3× service and minimum burst ≥6× service per PHMSA special permit/standards).[2][3][4]

Filling involves evacuating air, adding solvent by weight, and charging with acetylene in controlled stages so the settled pressure does not exceed 250 psig at 70 °F (DOT limit).[6]

Valve/connection notes: Fuel-gas cylinders (like acetylene) use left-hand CGA connections (e.g., CGA-510/520) and oxygen uses right-hand CGA-540, minimizing mix-ups.[10]

Safe Storage and Handling of Acetylene Tanks: Rules That Save Rigs

Key OSHA takeaways for the shop floor:

- Use pressure right: Never generate, pipe, or use acetylene above 15 psig (≈30 psia). This limit does not apply to storage in the cylinder but does apply to use pressure.[1]

- Store upright: Acetylene cylinders shall be stored valve end up in a ventilated, dry area away from heat sources.[1]

- Segregate oxygen: Keep oxygen cylinders at least 20 ft from fuel-gas cylinders or separate with a 5-ft, ½-hour-rated noncombustible barrier.[1]

- Ventilation: Acetylene is lighter than air (relative density ≈0.9), but can accumulate near ceilings—ensure effective ventilation and avoid unventilated enclosures.[7][1]

- Thermal protection: Cylinders have fusible plugs designed to melt around 212 °F to relieve pressure in a fire.[8]

Step-by-Step Guide to Setting Up Your Oxy-Acetylene Rig with a Fresh Tank

Alright, hands-on time. You’ve got your Victor or Harris torch, green oxygen hose, red acetylene hose.

Step 1: Inspect the cylinder—cap off, valve clean, no dents; secure it upright with a chain.

Step 2: Crack each valve momentarily to blow out dust, then attach regulators with the correct CGA fittings. Open the oxygen cylinder valve fully (backseat), then back a quarter-turn. For acetylene, open no more than about ¾ to 1½ turns so you can shut it quickly in an emergency.[9][4]

Step 3: Set pressures by tip manufacturer’s chart (examples below). Do not exceed 15 psig acetylene at the regulator.[1]

Step 4: Purge lines, light with a striker (not matches), and adjust to a neutral flame (sharp inner cone).

Step 5: Install and maintain check valves and flashback arrestors as required by your setup—these devices prevent backflow and stop a flashback from entering the fuel line.[1]

Shutdown: Close acetylene first, then oxygen; bleed pressures; back out regulator screws slightly; cap the cylinders.

| Task | Acetylene (psig) | Oxygen (psig) | Typical Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazing Copper Pipe (1/2″) | 3–5 | 5–10 | #0 |

| Welding Mild Steel (1/8″ plate) | 5–7 | 10–15 | #2 |

| Cutting 1/4″ Steel | ≤10 (do not exceed 15) | 30–40 | #00 |

| Gouging Cast Iron | 8–12 | 20–30 | #3 |

Common Mistakes with Acetylene Tanks and Quick Fixes

1) Overdrawing the cylinder. Going past the recommended withdrawal rate (≈1/7 of capacity per hour; sometimes ≈1/10 for small cylinders) can pull solvent into your lines. Solution: reduce flow, warm/upright the cylinder, or manifold multiple cylinders.[10]

2) Horizontal storage or use. Transport cylinders upright. If one has been horizontal, stand it upright and allow time for resettlement (commonly at least an hour) before use.[6]

3) Ignoring requalification. Cylinders must meet DOT requalification schedules; if a cylinder shows damage or fails checks, return it to the supplier.[2]

4) Mixing hoses or fittings. Use red for fuel (left-hand threads) and green for oxygen (right-hand). Match CGA connections correctly.[10]

Pros and Cons of Using Acetylene in Your Welding Setup

Acetylene’s the OG fuel gas, but it’s not perfect. Here’s the quick take:

Pros:

- Hottest common fuel-gas flame in oxygen (~3,150–3,200 °C neutral), enabling true gas welding of steel.[5][12]

- Versatile: welds, cuts, brazes, solders—one rig does it all.

- Portable: no power needed; useful for field repairs.

- Fast preheat: typically faster than propane on thicker sections.

Cons:

- Requires strict pressure limits (≤15 psig use) and careful handling.[1]

- Solvent carryover possible if overdrawing; may need manifolding for high demand.[10]

- Storage/segregation rules are tighter than for some alternatives.[1]

Compared to propane: acetylene runs hotter in oxygen (better for gas welding), while propane excels for heating and cutting economy; both cut steel with the right tips. Typical oxy-propane peak temps are lower (~2,800 °C).[12]

| Attribute | Acetylene | Propane |

|---|---|---|

| Flame Temp in O₂ (°C) | ~3,150–3,200[12] | ~2,800[12] |

| Best Use | Gas welding, precision brazing | Heating, cutting economy |

| Stability in Storage | Requires solvent/porous mass | Compressed liquefied gas |

Machine Settings and Joint Prep Tips for Flawless Oxy-Acetylene Work

Settings vary by thickness—start conservative and follow tip charts. For a 1/8″ mild-steel T-joint, an example is ~6 psig acetylene and ~12 psig oxygen with a #2 tip; preheat to dull red and use ER70S-2 rod. Cleanliness matters: remove mill scale and oils (solvent wipe, then dry) to avoid porosity.

For cast iron, slow preheat and controlled cool help prevent cracking; for aluminum, appropriate flux is essential when gas welding.

When to Choose Acetylene Over Other Welding Processes

Oxy-acetylene shines in maintenance and field work where power isn’t available, and as a training ground for heat control and puddle manipulation. For structural productivity, stick/MIG often win; for portability and versatility on mixed metals, oxy-fuel holds its own.

Advanced Techniques: Flame Adjustments and Filler Rod Selection

Neutral flame is the steel-welding sweet spot. Carburizing flame (excess acetylene) can be used for certain hardfacing; oxidizing flame supports cutting. Match filler type/diameter to base metal and tip size; keep rods dry to prevent spatter and porosity.

Troubleshooting Acetylene Flow Issues in the Shop

Flow drops? Check for clogged tip or regulator filters (solvent mist can foul them if the cylinder was overdrawn). Popping flame? Clean/ream the tip and verify pressures. Overheated cylinder? Isolate and cool from a distance; if involved in fire, expect fusible plugs to activate around the boiling point of water.[8]

Integrating Acetylene into Modern Hybrid Welding Setups

Blend processes smartly: oxy-fuel preheat before TIG/MIG on thick sections, plasma for roughing then oxy-fuel for bevel/gouge, and manifolds for steady industrial draw. Maintain check valves/flashback arrestors across all configurations.[1]

Conclusion: Arm Yourself with Acetylene Knowledge for Safer, Stronger Welds

From the solvent-soaked porous core to the 15-psig use limit, now you know why acetylene demands respect—and how to get clean, consistent results. Keep cylinders upright, respect withdrawal limits, set valves correctly, and use protective devices. Your reward: stable flames, fewer hassles, and solid work.

FAQ’s

Can I Store an Acetylene Tank on Its Side?

No—store and use upright. If a cylinder was on its side, stand it upright and allow time for the solvent to resettle before use (many suppliers advise at least one hour).[6]

How Do I Know If My Acetylene Tank Is Low?

Because the gas is dissolved in solvent, pressure isn’t a precise contents gauge. Track usage, check supplier capacity charts, and weigh if necessary for an accurate read.

What Happens If Acetylene Leaks?

Evacuate, ventilate, and remove ignition sources. Shut the valve if safe and leak-test with approved solution. For significant releases, follow local emergency procedures per OSHA/NFPA guidance.[1]

Is Acetylene Safe for Indoor Welding?

Yes—with proper ventilation and protective devices. Acetylene is lighter than air (≈0.9 relative to air) but can accumulate—use local and general exhaust, keep cylinders out of unventilated spaces, and install check valves/flashback arrestors.[7][1]

Why Does My Oxy-Acetylene Flame Turn Yellow?

Likely solvent carryover from overdrawing the cylinder. Reduce withdrawal rate, let the cylinder warm upright to ambient, purge lines, and clean the tip. If persistent, consult the supplier.[10]

References

- OSHA 1910.253 – Oxygen-fuel gas welding & cutting (use pressure ≤15 psig; storage/segregation; protective devices).

- 49 CFR §178.59 – DOT-8 acetylene cylinders (service pressure 250 psig, construction/testing).

- 49 CFR §178.60 – DOT-8AL acetylene cylinders.

- PHMSA SP10320 – Test/burst multipliers for acetylene cylinders.

- BOC – Facts about acetylene (porous mass, stability, flame temperature).

- BOC – Using acetylene safely (upright storage/use; settling after horizontal).

- Air Liquide SDS – Acetylene, dissolved (relative density ~0.9; dissolved in acetone/DMF).

- Air Products Safetygram-13 – Acetylene cylinders (fusible plugs ~212 °F; valve guidance).

- MillerWelds – 10 steps for safe oxy-fuel torch setup (oxygen backseat; acetylene valve opening).

- Harris Products – Acetylene FAQs (withdrawal rates; solvent carryover) and Airgas – CGA connections (LH fuel-gas).

- UKHSA – Acetylene: general information (odor when impure).

- Air Liquide UK – Oxy-acetylene welding (flame temperature up to ~3,200 °C).

- 49 CFR §173.303 – Charging limits (≤250 psig at 70 °F, settled pressure).